In this interview, Ann-Sophie Barwich, Assistant Professor at Indiana University Bloomington, talks about being baptized in protest in East Germany, acting, poetry, Faust, Die Toten Hosen, Demian, an early interest in drama and art, dabbling in literary studies in college, and then philosophy and science, dealing with loss, working with John Dupré, the problem with armchair philosophy, Hedwig Dohm and feminism, models and the practice turn in philosophy of science, starting a dissertation on Leibniz and ending up with a dissertation on the history and philosophy of the science of smell, Stuart Firestein, language and philosophy, The Rusty Bike, sexism, petrichor, her new book on the philosophy and science of smell, Ambergris, dogs, beer and Indiana, Gestalt switches, Martha Nussbaum, EEG, the Churchlands and John Bickle, The Philosopher Queens, Lost in Translation, Blondie, Leonard Cohen, Pollock, Death in Venice, Kandinski, Murder She Wrote, Tesla, and her last meal…

[3/27/2020]

First smell you can remember?

I can't. Can you? Maybe the rubber-metal-wood-dust smell of my father's garage. Maybe cooked Brussels sprouts, which I truly loathed as a kid. But I honestly can't say.

Where did you grow up?

I like to joke that I was born in a country that doesn't exist anymore, East Germany. My birthplace is historically really interesting: Weimar. It's a picturesque little town that embodies the best and worst part of German history. It was home to many classic writers and composers -- Goethe, Schiller, Herder, Wieland, Liszt, Hummel -- yet, later, they built a Nazi concentration camp nearby (Buchenwald), which was repurposed into an internment camp during Soviet times.

What did your parents do?

My parents were much more interesting than I gave them credit for as a kid. They separated when I was born but stayed close friends until the bitter end.

My father, who died a week after my 21st birthday, was a mechanic - although he held a variety of jobs (janitor, the driver for a local resident's home, things like that). The smell I associate with him is his DIY bench, building things. He was a tremendously creative swearer!

My mother raised me and is the opposite: diplomatic, much more agreeable than my father (or me for that matter), a quiet strength. She's a retired schoolteacher, read Goethe and Schiller's poems to me instead of bedtime stories. What's eerie is that she's got this Benjamin Button thing going on. She's become more youthful in her appearance with age. It's really uncanny. And inherited, I hope.

What was your family like? Supportive? Happy household? Religious? How were you most similar from the rest of your family? Dissimilar?

My mum's side is a wonderfully quirky bunch. If you came to a family get-together, you'd find two kinds of temperament: those starting a heated political discussion over passing the salt, and the ones rolling their eyes. I'm on the argumentative side. My family also shares a history that has shaped their hopes concerning the next generation, especially in their attitude to food and education. My grandparents and their children were refugees from the Free City of Danzig (now Gdánsk in Poland). My oldest uncle was 13 at the time, two younger children died on the way. My mother was born several years afterward, as a late but lucky accident.

Next to my mum, one of my uncles and cousins had a great impact on me. My mother gave me the freedom denied to her. It was East Germany - she wasn't allowed to study medicine, her dream, as she wasn't dancing the party line and singing the right tune. In fact, I was baptized in protest to the government. A non-conformist act back then. Otherwise, not really a religious family. Respect for other's beliefs, but mainly there for the Christmas carols, really. Meanwhile, my uncle challenged every opinion I had as a kid (which he did until the end, as he very recently died now, too). But I also remember that once I came up with something he didn't know, he looked it up, and we talked about it. This is how knowledge, for me, acquired its deeper potential for democratic engagement. One of my cousins is very similar.

As a little kid, what did you want to be when you grew up?

Mini-me wanted to be a cowboy. All about horses - and the hat.

Teenage mischief?

To be honest, I was a pretty dull teenager. No trouble, just snarky comments and lots of decorative adjectives…. because I wanted to be a writer or an actress! I was infatuated with poetry and wore a moody black coat. I enjoyed acting, that strangely palpable yet invisible tension on stage. You can show something without being seen. The fact that you don't just don a bit of make-up and some clothes, but you actively walk the line of thought by someone else, minimizing the distance between you and whomever it is you are portraying. But reading was always an underlying theme.

Books?

There were several books. I could recite endlessly from Goethe's "Faust." Fell in love with Goethe's "Die Leiden des jungen Werther" and Hesse's "Demian" – very teenage existential angst with a historical twist. The two books that started to shape my socio-political interest, however, were Heinrich Mann's "Der Untertan" and "Effi Briest" by Theodor Fontane.

Music?

My favorite bands were Die Toten Hosen and Die Ärzte.

Good high school experience?

Loved learning, hated high school. Not a conflicting statement, unfortunately.

Interested in sports?

Does animated cheering count? Then football (the real one, played with your feet). Don't mention the last World Cup, though.

What would your teenage self make of your current self?

Teenage me would scold me for not finishing the novel (it's in the drawer and needs more time, ok?!). But she'd love to hear that she'll live in cities such as Berlin, Vienna, ... and New York! That she's going to meet some really amazing and inspiring people that could be straight out of a novel. That she's finding the thing she's really good at. Plus, one day she'll be upgraded to business class wearing an awesomely hideous reindeer jumper, Bridget-Jones style. Some things never change.

If you could give yourself advice back then, what would it be?

So many things actually. Perhaps most importantly: Take your time. Listen. Read between the lines and trust your gut. Whatever situation, there are no right words. There are good choices and not so suitable ones, sure, but stop thinking that you'd be understood if only you find that word. That right kind of word. Misunderstanding is a condition of communication. To whom you are talking will shape how you say something much more than what you intend to say. And when you find something lovely about someone, just tell them.

Did you start thinking about college, if college was even on the table? Where did you apply? What was the plan?

Oh gosh, no, there never was a plan. To be brutally honest? I was rejected - for the writer's program in Leipzig (which graduated authors like Julie Zeh). So I decided to try Literature Studies. Close enough, I thought. I only applied to Berlin (because... Berlin!) and accepted the first place offered at the Humboldt-University. In hindsight, I was astonishingly green if not a bit too romantic about the whole thing. Compared to the current generation that's planning, sculpting, measuring its CV from day one. I lacked guidance or any hunch about what I now know academia to be. How, if you're not from that background? Mind you, the Internet was still new-ish. So I just followed whatever fascinated me. That's when I fell for Philosophy. I needed a second subject and dabbled in Biology, Theology, and Medieval Studies. Philosophy took over. At that time, I also did several academic internships, for example, at the Helmholtz-Center at the HU and the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences (they still have an original paternoster lift!). The latter organized a workshop with John Dupré as an invited speaker. John was incredibly kind, lots of Monty Python jokes, he continued to borrow - and kept... - my lighter. So I read up on his work, which was something entirely new to me, and he suggested that if I'd ever considered doing a Ph.D., I should contact him. That was the time when I started thinking about my future more consciously. I liked his thinking, got increasingly fascinated by Biology, and so I decided I wanted to work with him. A year later, I dropped John an email with the subject: No one expects the Spanish Inquisition.

What did you find appealing about philosophy, exactly?

Difficult question because I developed an ambivalent relationship with philosophy. I'm deeply convinced of the value philosophical thinking has in science and society. However, its institutionalized profession disenchants me. It too often is an exercise of form over the creation of content. An extreme example is metaphysical debate on "grounding." Perhaps, this is a consequence of the specialization in the natural sciences in the nineteenth century and the fact that philosophers gave up topics now covered by the social sciences in the twentieth century, but large parts of the discourse have become somewhat self-referential. That's not to say that there aren't any good philosophers or debates - there really is some exciting work going on. But these people too often work at the margins, not a great incentive given the current job market pressure. So my distaste for intellectual hand waving is a direct consequence of the potential that good philosophical practice has, but is incentivized to suppress. Before you object, I end with a quote by Habermas, which for me sums up the issue: "Philosophy's position with regard to science, which at one time could be designated with the name "theory of knowledge," has been undermined by the movement of philosophical thought itself. Philosophy was dislodged from this position by philosophy."

Best objection to this characterization of philosophy?

Ha! I bet most readers have formulated a strong objection at this point. Many may feel that my criticism is uncharitable and that I undervalue philosophy. I hear that a lot. But it really isn’t. On the contrary, I see a much broader potential and power of philosophy than some academic debates would indicate. There’s a reason why people like Hannah Arendt eschewed the title of philosopher despite doing heavyweight philosophical thinking in her work. There is a reason why we now have philosophical articles on the proper treatment of the Churchlands (are they *really* philosophers?) – just because they are doing philosophical thinking that steps out of the comfort zone of many armchairs and into the realm of science. Notably in a proactive and complementary fashion. Philosophers tend to recognize philosophy only as what they were exposed to as philosophy. But we have become so limited in what’s been put on the curriculum and what’s been acceptable as philosophy in the higher-end journals that the necessary broader historical, global, and methodological scope is often missing. Sure, Africana and Asian philosophy have gained some momentum more recently, yet it’s still viewed as a somewhat niche expertise. It’s not niche, though. And so I merely encourage philosophy to get out of its currently still restricted and highly contingent institutionalized self-image. If we forfeit a pluralism of what philosophy is, can be and can do, we are not just losing touch with the world, including science and society, we furthermore are actively narrowing down philosophical practice itself. Preventing that requires some serious soul-searching about a lot of traditions, including topics and styles, some of which have become far too self-complacent. We have to do more philosophy about the question of what (modern) philosophy is and can become. What’s so objectionable about that?

How did your worldview evolve in college?

It changed much later, after grad school. A great lesson was to understand the subtle difference between what people say they believe from what they actually do. Politically, the intellectual left particularly disillusioned me, having largely forgotten the working class and repeatedly putting women's rights second place to "the greater moral good," whatever that is. The things you once approached with more hope always end up disappointing you. There's just always something politically more urgent than equality of the sexes. How long do we have to wait until it's a good time for the world? The revolution that really changed women's rights was suffrage, not some grander societal goal. So I've recently started reading about Hedwig Dohm. She advocated the women's vote as early as 1873, as well as University access for women and their right to work. She published sharp-witted manuscripts and cautioned against the war hysteria before WW1. She lived to see the women's vote in Germany in 1918; Dohm was 87. I owe her more than Marx, Liebknecht, or Trotzky.

What did your parents make of your decision to go into philosophy?

I think they had hoped I'd do something more practical, like medicine. But they let me run with it. Alas, it made Christmas gifts easy: Here's a new book.

You mentioned your dad died when you were in college. How did you deal with that?

My father died, two of my aunts died (with one I was very close), another family member died,... recently now my favorite uncle died, so I thought a lot about the brittleness of the present.

Where did you end up going to grad school? Biggest surprise?

I did my Ph.D. at Egenis, the Centre for the Life Sciences at the University of Exeter. One of the first surprises was how different academic Philosophy was done in the Anglo-American world, compared to Germany, for instance. I think we still underestimate the regional differences between Philosophy across the globe and the dominance of Philosophy originating in the UK and US. Compare how many philosophers from the Graduate Center at CUNY you could name from the top of your hat with how many Russian or Brazilian philosophers would come to mind just as quickly.

Philosophically, what was trending at grad school at the time? In general? What were the strengths of your grad program?

Trending in the UK HPS-community was the practice turn, the whole models and scientific representation debate. The strength of the program at Egenis was its intellectual freedom and, at the time, great community and interdisciplinary exchange. There was a lot of support and encouragement to present talks, at the Center as well as at external conferences. The weakness, in hindsight, was that it did not prepare its grads for the academic market. It was a bit of a shock when I saw the training Columbia grads received for the job market. It felt as if I had entered a formula one race on a tricycle.

Who did you talk with most about philosophy? Who did you hang with?

What made grad school special for me (and for many people, I believe) was the comradery. It's a big part of your life, and you get to share it with a group of people going through the same intellectually transformative and individually challenging rite of passage. At Egenis, we had a great group of grad students, all started at the same time but from different disciplines. We also talked about Philosophy, but often in its relation to science or society. That theme continued throughout my postdoctoral fellowships at the Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research, near Vienna, and at Columbia, where I was in a program that fostered integration of neuroscience with humanities. I was always surrounded by philosophically interested people from different disciplines. Hardly “pure philosophers”. Naturally, this interdisciplinary trajectory has shaped the way in which I understand and discuss Philosophy as a practice outside its confined institutional environment.

Did you feel insecure, at all?

The question I regularly encountered, and still do, is: Is that still *Philosophy*? This undermined a lot of my confidence in the beginning. This ominous "more" of Philosophy as this invisible essence that somehow was not detected in my work. My writing was too scientific, too historical, too contemporary, too this and too that. Just never "enough Philosophy." It took me years to realize that there is no philosophical essence. It's an intellectual convention. Too often this conception is bound to a form of expression, how you situate yourself in relation to other sanctioned authors, not a way of asking and thinking through content. The critical switch then happened when I read people like the Churchlands and Dennett. Guess what question I read in reviews of their books: Yes, yes, nice, but is this still Philosophy? Let me reply now: If you think that it's reasonable to tackle questions of conscious experience with, say Bertrand Russell, in the 21st century - despite the revolutionary advances in neuroscience - how can this *still* be Philosophy?

What was your dissertation on?

How the material understanding of odor changed with advances in scientific practice. Smells are an interesting ontological phenomenon, ephemeral sensations yet indicative of some deeper material essence. You don't eat food that smells rotten, no matter how fresh it looks! Just how would you measure a smell? How would you determine its effective causes? Half of the thesis focused on smells as natural kinds and the conceptual changes in their historical classification. The other then focused on modeling in the twentieth century, specifically the shift from odor chemistry to biology, for an argument on scientific pluralism.

Did you have any interest in smells before the dissertation? Are you…good at smelling?

Admittedly, no. Of course, I read Patrick Süskind’s The Perfume during my undergraduate studies. But that was about all of my exposure to this molecular multiverse. Like many people, I never really paid attention to odors. Today, my nose is much more refined. The reason for that is because perception is a learned skill, and trained perception will increase both the accuracy and scope of your sense of smell. So you may think you’re not good at smelling, but give it some training, and you’ll notice the difference soon enough.

How did dissertating work? How'd your views change?

I actually changed my dissertation topic halfway through. That wasn't advisable (in the UK you only have 3+1 years). But I was stuck in an intellectual crisis early on. Initially, I planned to apply Leibniz's concept of identity (sequential rather than sets of features) to biological classification (organisms, species, etc.). Then I heard that Justin Smith was writing a book on that topic. I didn't want to write a second-rate thesis to someone else's book - I say second rate because I also wasn't convinced of my topic anymore. There was one question I couldn't answer: So what? Sure, I could finish this conceptual exercise. But to what end? I grew frustrated with philosophical scholasticism, I wanted more. By accident, I saw a talk on smell and thought: 'Huh, I have no idea how we smell!' Well, turns out that's indeed the question. I started reading on smell, and couldn't stop. It was fascinating. My nighttime reading soon moved into the time for my thesis work - until the point was reached that I thought: I may as well do this topic full time. Luckily, John was on board. I couldn't justify it beyond my gut feeling: This is it. I think most people at Egenis thought I was this weird kid with this obscure topic!

Do you remember who gave the talk on smell?

Yes. It was a TED talk by Luca Turin, where he popularized his quantum theory of smell that was also turned into a bestselling (not peer-reviewed) book. I was totally smitten with this idea at first and intrigued by the story of its inventor. However, over time and with increasing work on the details and research on olfaction, I changed my mind. In fact, I recognized a big gap between how science is done and how it is perceived from the outside. I felt that my philosophical training about epistemic and social norms in scientific practice had utterly failed me in this case. I then published an analysis of this case to demonstrate why and how philosophy can also fail us in our understanding especially of ongoing science.

Other than John, inspirational teachers?

Yes! Now, this has to be a longer answer because I've been incredibly lucky with mentors throughout my academic life. Good mentors are worth their weight in gold. So do let me introduce them:

During my Magister, I took every seminar by Lutz Danneberg (a German literature theorist). He was in his late 50s, arrived in this Miami Vice suit, tanned with 1980s pilot-porn sunglasses, wild lion-like hair, and a proper Nietzsche 'stache. He also read like an insomniac, in four languages, and across disciplines. His specialty was methodology, and I finally found my intellectual inspiration.

Then there was Hasok Chang. He's been my external examiner and became a friend throughout the six years on the job market (and hundreds of recommendation letters). But he influenced me already in my first year as a grad student. I sat in the back in one of his talks about the boiling point of water, where he presented an experimental recreation. And I was struck to the core: a philosopher doing experiments?! Heresy! Well, that's what I wanted to do, in my own way. He also radiates this warm kindness, which taught me that academic respect has something to do with sympathy for others. We tend to forget that here and there.

I also had great mentors during my two postdocs. There was Werner Callebaut at the KLI. He was a cartographer of knowledge and of disciplinary history. He had this trademark Belgian accent (I have his pronunciation of “bus” engraved in my memory), was genuinely passionate about research, and turned me into the radical naturalist I am today. In fact, he knew what I needed even before I did - I remember walking to his desk, saying: 'I think I need to know more about the evolutionary roots of the olfactory system.' He pulled out a book from under his desk, grinning and saying: 'I ordered this for you last week.' Unfortunately, he died in November 2014. It was very sudden. I lost a mentor and a good friend.

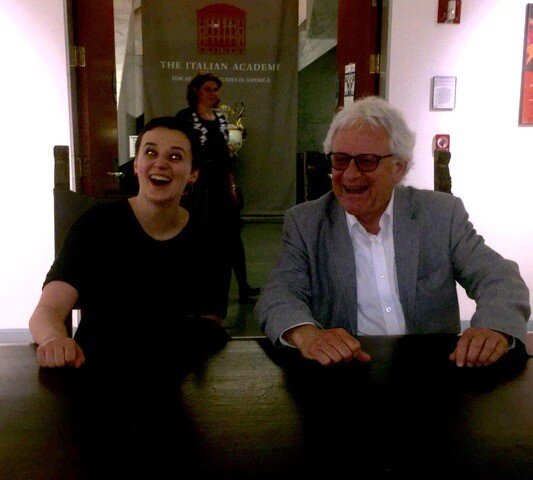

Ann-Sophie and Firestein

But the person who would change my life was Stuart Firestein. I spend every day, for three years, in his laboratory at Columbia. He's not your garden-variety scientist. He began as a theater director in Philadelphia, went into neurobiology in his thirties, got his PhD when he was forty, became one of the most prominent olfactory neuroscientists, and now writes popular science books with a solid history and philosophy of science outlook (with provocative titles such as Ignorance and Failure). Hasok got us into contact, and we hit it off right away. Stuart's brain is an intellectual firework, paired with this sharp Upper West Manhattan humor. We recently had a beer, realizing that we swapped roles by now: He became more of a philosopher (doing archival work on nineteenth-century French philosophy of science), and I turned more into a scientist (starting my own EEG/olfactometry lab soon). That said, it was Stuart who made me a better philosopher. You realize the real potential and value of philosophical thinking in science when you engage with, well, science at the bench and - more importantly - scientists.

Been very lucky finding people who were inspiring and kind along the way, further including Terry Acree, Andreas Mershin, Barry C. Smith, Chris Peacocke, Jutta Schickore, Peter Todd, Gordon Shepherd, and Aina Puce. They all gave me their time and let me run with ideas.

How did grad school hone your skills as a philosopher?

Egenis opened up an entirely new perspective on philosophical work for me; namely, that you can fruitfully participate in scientific discourse. I was hooked. Although my work now went too deep into scientific practice even in the view of many Egenis people. But it all started there, they created this monster.

How did moving for those post docs effect your philosophical development?

Thinking in another language changed the way I understand communication. I consider myself lucky to be able to reason in two languages (it does make a difference) - but the road to bilingual thinking included barriers that required patience on my part. If you have an accent, some people unconsciously treat you as less intelligent. This isn't personal, but you have to acquire confidence in your abilities - and learn to adopt language use also as an attitude. Consider the difference between Oxford English and New York. The communication of meaning is not just about the transfer and extraction of content.

Any major world events that had a significant impact on your life and worldview during grad school?

The first female chancellor of Germany. With a Ph.D. in Quantum Physics and Chemistry. Speaking of 'you have to work at least twice as hard as your male peers'...

What did you do in your spare time? Advice?

I am a German. We do not do spare time. Just kidding, photography. And writing a novel. It's been 'in the drawer' for a while now, biding its time until I commit myself to work on it again. I also had a local pub in Exeter, called The Rusty Bike (ceased to exist). I liked reading there because you also meet people from all walks of life. Farmers, solicitors, gardeners, chefs, actors, academics, accountants, waiters... I learned English by talking to people about their life and worldviews over a pint. This experience would help me a lot when I started interviewing scientists about their research years later.

Tell me more about these interviews with scientists!

That was the most fantastic time! Have you ever wondered how it is to observe a science at its frontiers, close to its breakthroughs? Well, that's what I was doing. For three years, I interviewed 44 olfactory specialists for my book on smell as a new model for theories of perception and the brain (coming out Spring 2020). Experts included neuroscientists, chemists, psychologists, perfumers, winemakers. These interviews were all different. They took place in laboratories, at conferences, over the telephone, with coffee or beer, sometimes for an hour, sometimes over several days (couch crashing inclusive). I started with a few questions I wanted to ask and, routinely, these interviews developed a life of their own. The field is full of characters, stories, incredible creativity, and passion for curiosity. These interviews are part of my book's narrative, bringing the science of smell to life for the reader. This is a field that underwent its formative stages only a few decades ago. So most of the key actors involved in its modern development are still alive and doing research. That's an incredible opportunity for a philosopher and historian of science - to capture a field in its formative stages yet still connected to its past.

The idea for the interview design originated with my mentor in Vienna, Werner Callebaut. He interviewed philosophers of biology and biologists for 10 years in the 1980s, resulting in his book: Taking the Naturalistic Turn, How Real Philosophy of Science is done. Werner also gave me some great advice about how to do interviews. Unfortunately, interviewing is an undervalued art today. You possibly have your own stories to tell here! And I do hope you write an essay or post about your perspective after talking to so many diverse philosophers. I'd love to read that.

Thanks! I have lots of ideas! Hey, how did you fund the production of your book? How did you find a publisher?

The book project was possible because I had a very generous postdoc at Columbia University - at the Presidential Scholars in Society and Neuroscience Program. I also used some of my own savings and the publisher’s upfront money for things like figures, some of the interview transcriptions.

How I found my publisher? One of the most beautiful stories, very New York. I actually tell it in the acknowledgments of my book. Some years ago, when I traveled home from New York for Christmas, I helped an elderly gentleman on the train in Germany with his luggage. It turns out, Peter Judd (who is an author) was also from New York, we soon became friends and went to the opera every two weeks. One night at the MET, seeing my favorite opera, we met one of his friends living in the same co-op. On the way home, she asked me what I do and, upon hearing about my work on smell, asked me to tell her something interesting about smell… and whether I was thinking of writing a book. Of course, I was (well, trying). Joyce Seltzer, her name, then revealed herself to be an editor with Harvard University Press and asked me to send her my proposal. The first draft, well, it needed work. I still remember that afternoon when she walked me through my own mind like some wizard. She really helped me to birth what would become the book I was going to write. She then forwarded my revised proposal to the science editors at Harvard Press. Just one day later, Janice Audet, my wonderful editor, dropped me an email. And things continued to fast-forward from then. So it’s not your usual how to land a book deal, I guess.

What was the interview advice Werner gave you?

That everyone wants to you tell their story. And you won’t get any answers to your questions, or anything aside, before they have made sure you heard, in full, the story they want you to understand first. If you try to steer the conversations to your intended questions, they will always go back to their story. So let them finish what they want to say. Then ask your questions. And listen, listen, listen closely. Prepare, read their works before you interview them to ask good questions. Of course, he told me more.. so I really recommend reading his book to get an idea of his style.

What's the novel about?

Coping with loss and its invisibility in our daily interactions. I started it after my father died. That was also a time when I read more belletristic. I now may have enough distance to revisit these memories, rework the draft from a writer's perspective, with a writer's voice, into a broader literary piece.

What was the job market like when you finished? Why’d you decide to pursue post docs after you wrapped up your dissertation? Did you also pursue tenure track jobs? Were you willing to take a non-tenure track job?

The market wasn’t great. It went further downhill since. And I fully realized just how bad it was over the years applying and applying again, and again, and.... Why did I start and kept on trying, nonetheless? Because I was naïve and hopeful, and we rarely connect such developments and statistics to our own life. It’s different, no, at least THIS time. It’s different in MY case. It’s very human to think that. After all, we’d be terrified all our lives if we didn’t have this psychological cushion. But it can hit really hard when that cushion gets crushed. I was preparing to leave academia before my Bloomington job materialized, almost 5 to 12, really last minute. I had been applying worldwide, to 10-month fellowships, grants, postdocs, TT-jobs, everything. I just never fit the bill. There just is so little opportunity and space for people crossing disciplines. So my job at Bloomington, well, it feels tailor-made for me. I am very aware of the minute chances of that happening.

Encounter sexism on the job market?

Does the pope wear slippers? Yes. Post Ph.D., I was six years on the market with a few experiences under my belt, good and bad. A few things crystallized: I know I already pushed some feminist thoughts a bit hard here, but I just cannot be content anymore. By now, everyone in academia is a feminist, publicly, but - strangely - we're still not hiring many women, despite an abundance of qualified ones available (and of candidates in general). For example, 1 in 5 professors in the UK is a woman. And overall UK universities are hiring less, not more, women. Personally, I was on one shortlist where I had 3 times as many publications as 2 of the guys. One of the guys got the job. There’s also dodgy politics at times. Let's just say one of my applications was rejected - before the committee had even met. Unfortunately, I heard comparable stories by others. Accepting this in academia is harder than in the industry, I guess, because there's this underlying expectancy, even attitude, of an ethical code. On the bright side, I also saw Departments with a variety of styles and people, and many were very kind. These experiences enriched my understanding of philosophical activity. I had many discussions with engaged thinkers about my research that later helped me finish a tricky part of my book. In hindsight, I got a lot more out of most interviews than meets the eye.

Don't have to answer this one but I wouldn't be doing my job if I didn't ask: why do you think they rejected your application before they met?

Internal politics. Perhaps they had their internal candidate, and I was a bit in the way. Wasn't just me. They did something oddly similar one year later.

Advice?

It’s the same that I got after a series of particularly harsh rejections, when Stuart Firestein, my mentor at Columbia, told me: “Don't get hung up on rejections, kiddo, you don't know the search committee dynamics - most of them can be surprisingly irrational. As depressing as it sounds: this has nothing to do with you.” So I’d say, focus on your research and the next steps instead. Be clear about your own priorities. What do you want to do, and what are you really after? Is it academia, or it is research, or teaching? These are not necessarily the same. Especially if you do non-mainstream, interdisciplinary work. Plus, the academic landscape is changing, and a couple of my friends have left academia to become independent scholars, crafting their own path in tandem with academic scholarship but independent of its official tenure. It's about time that the academic community stops chastising independent scholars, as this is going to be a considerable part of future scholarship - and innovation. It's a new opportunity for collaboration as well.

Favorite smell?

Ha! Come on, I would have been disappointed if you hadn’t asked. Many favorite smells. They all are somewhat green: Petrichor (the smell after rain), Jasmine, fresh cut green grass.

How would you describe Petrichor to a person who doesn’t have a sense of smell?

The sexy sensing of bacterial spores being released into the air after rain. Kinda green and dirty but, oh, so satisfying to inhale.

Least favorite smell?

Nice try, not revealing my Kryptonite.

Fair enough! Most interesting thing you've ever smelled?

Ambergris: hardened whale dung (although there is a serious debate about whether it is closer to vomit or excrement). It's one of the most luxurious and expensive natural ingredients in perfumery. Only 1% of sperm whales produce the stuff, you can't farm it, and one gram of high-quality ambergris pays more than one gram of gold. Sperm whales eat octopuses, whose beaks can get caught in the intestines, where these beaks start blocking and collecting whatever gets flushed through, including shit. Some sperm whales die, and while they rot, the aggregated clot is freed and drifts for a long time on the saltwater, hardened by the sun. It smells of seawater, hay, tobacco, bit fecal, too. Very complex.

Things most people don't know about the sense of smell?

There are so many myths about your nose! Most myths have been debunked by science yet continue in popular imagination. For example, taste is actually an olfactory sensation; it is retronasal smell to be precise. You don't have strawberry taste receptors, nor do you have taste receptors for mint or vanilla aroma. Likewise, we're not bad at naming smells; we generally just don't pay attention and aren't trained. Moreover, we can use odors to navigate space, just like dogs. Lastly, our sense of smell is not in evolutionary decline of impoverished. To the contrary, olfaction is an excellent example of how misleading idle armchair speculation can be. Philosophers should care more about smell!

You've been at Indiana for the past year. How would you describe Indiana to a person who has never been?

Fields and clouds, endless horizons, and dramatic sunsets in summer. Just yellow and blue, with a dash of pink. Excellent microbrewery and food culture and incredibly kind people. Although to be sure, I had no idea what to expect after my move from New York. I mean, I love New York, and so I remember when my best friend and I entered Indiana on our 3-day road trip, and all we saw were the same shop signs every few meters: guns, flags, fireworks, guns, guns, flags, more fireworks, and guns. And, for a moment, I honestly thought: What the fuck am I getting into now? But once I arrived, I really liked it. People are sincere in their kindness and go out of their way to help you feel welcome and settle in. Bloomington, in particular, is like a little bubble, like some small town in a parallel world, a bit unreal in its dreamy state. It gives you time to think. Oh, and one last thing about Indiana: We had Kurt Vonnegut. HA!

The departments you work in?

I live the best of both worlds! I have a split appointment at the Department of History & Philosophy of Science and the Cognitive Science Program. The HPS group is pretty diverse in their interests (from alchemy to logical positivism to cancer research, evolution, orgasm - yes, orgasm - and methods in science). They encourage and envisage an empirical direction for HPS. So imagine how thrilled I was to join them. Then there is the Cognitive Science Program, which is one of the best, really. I don't say this just because they pay my bills. It's an impressive group. They take interdisciplinarity seriously, ranging from computational modelers to neuroimagers, experimental humanities, and more. It's an excellent environment for me, as my colleagues are interested in new ideas and give you lots of support for testing them. So, if you're a student reading this, looking for an HPS-CogSci combo, do contact us.

Now that you have this lab at your disposal, interesting projects on the horizon?

A couple! Although, the lab needs to get started first (the building currently gets renovated, lab start is estimated to be early 2021). I will need to start with the more basic experiments, to obtain preliminary data for grants. I can tell you this much already: I am interested in the cognitive patterns and neural fingerprints involved in Gestalt switches and ambiguous stimuli in olfaction, combining EEG with olfactometry. I am thrilled, maybe also a little intimidated, but above all: curious!

Philosophical archenemy, that is, the best philosopher you disagree most?

Oh, good question. I don't have an archenemy… perhaps because I tend to pull a Putnam here and there, meaning I can also change my mind after a while. For instance, I recently started rethinking reductionism. I was trained by John Dupré! His program is pluralism, anti-reductionism and anti-mechanism. I had similar thoughts. After several years in labs, I found reductionism in practice a different matter from its philosophical treatment. I realized we need a better conceptualization of reductionism, less straw-man battles. Now I agree more with the Churchlands, Patricia and Paul, and John Bickle. To be sure, I think John Dupré might be more entertained than anything else by this.

Too few philosophers rarely seem to alter their views, which I find puzzling. How could you trust someone's intellectual curiosity and sincerity about understanding, if they never seem to change their mind? I share your appreciation for naturalism, but sometimes, it makes me wonder whether what is traditionally considered philosophy only has value to the extent it engages with science. Thoughts?

Philosophy has lots of value, not just to science! I rediscovered my love for philosophy that engages with the human condition, with society, political theory, the pragmatics of communication – modern challenges in light of our diverse intellectual heritage. That's why I think that Martha Nussbaum really is one of the most notable philosophers of our time.

Now, philosophy of science should engage with science. I know I have little patience with idle speculation about this thing called science from the armchair crowd. It's like an immoral priest – what's the point of your association with the church then? One frequent comment is that philosophy of science can have a value in and of itself, independently of science. I never know what this is supposed to mean, or why this is supposed to be philosophy *of science* then. Beyond the mantra, I have yet to see a profound defense of that claim. Try me, I can change my mind.

In the end, I think there is this fear of being measured by utility that's very common in Philosophy. Like inherent methods and results envy, a fear of being obsolete, which has led to a misunderstanding of Philosophy's relationship with utility. Yes, you cannot approach philosophy by strict consideration of utility, but that does not mean that you should reject methodological reflection on its utility and advance.

How do you see the future of philosophy? Exciting or disconcerting trends?

Philosophy has repeatedly been proclaimed dead. I think it'll go on. And I do believe it can remain one of the most significant contributions to society - if it wants to. For its future, I hope Philosophy does some soul-searching, however, when it comes to its institutional and personal history. We like to think of our profession, our studies, as training 'critical thinking'. But both in the Third Reich and East Germany it was the Humanities, Philosophers, who fell far too quickly, saluting to the new doctrines of the regime. The intellectuals, her friends and colleagues, disillusioned Hannah Arendt. They were contemplating about thinking, morals, and rationality. They should have known better, no? Also, it was a Philosophy student who killed Moritz Schlick. We should start also thinking about the darker parts and histories of our professional heritage. If we can honestly handle this, I have high hopes.

You're very active on twitter! Social media: good or bad for philosophy?

I am torn about social media, despite or perhaps because of my activity. It certainly taught me a lot about human interaction, communication (plus the lack thereof), and that - in the end - we often hear what we want to hear. So I started thinking about Paul Watzlawick's pragmatics of communication a lot again. And, to be honest, I recently decided to mute quite a few philosophers on Twitter (not you!), but concentrated on the scientists and historians. That said, there also are exciting people and works I discovered via Twitter. Like the book "The Philosopher Queens". What a magnificent idea and proactive way of doing philosophy in the 21st century! Overall, I think social media is a great tool to enhance the visibility of creative ideas - especially questions that used to be sidelined in favor of the more inside-baseball debates. So Twitter is a good way to find new papers or alternative approaches in the pipeline, outside the gatekept outlets. It is also a promising resource for cross-disciplinary exchange and collaboration. Scientists hardly browse philosophy journals, but they might discover your Twitter and find your approach relevant to their work.

Tell me all your thoughts on philosophy blogs...

A useful resource of public engagement. Also, for those wanting to do such blog, a great way to train writing.

Favorite books? Movies? Music? TV shows? Art in general?

Book: The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov, Goethe's Faust, Thomas Mann's Death in Venice, Effi Briest by Theodor Fontane, Der Untertan by Heinrich Mann, Klaus Mann's Mephisto.

Movie: Lost in Translation by Sophia Coppola, Hannah Arendt by Margarethe von Trotta.

Music: Blondie! And The National, Snow Patrol, Leonard Cohen, Schubert, Mozart, Aerosmith... many different bits and bobs.

TV Show: Game of Thrones (despite the last season), Wilsberg (German one), Poirot with David Suchet, and -don't judge me- Murder She Wrote.

Art: Pollock, Rothko, Toulouse Lautrec, Claudel and Rodin, Kandinski, Mucha, Turner...

About all: Just too many to name.

What are you doing during this pandemic?

Thinking. This whole thing, while visible with rational foresight, still unraveled at such a speed that my mind is gradually grasping what's going on. In an odd sense, my personal belief lags a bit behind my more unsentimental evaluation and anticipation. Generally, of course, I am staying home, do the physical distance thing, make a lot of virtual calls - to my family in Germany, my friends in New York, and now also my friends and colleagues here in Bloomington. But, I'll be honest with you, the first week just knocked me out, paralyzed me, because it does touch upon the fabric of everyday life and your tacit understanding of normality. Pardon my French, but it just fucks with your habitual, embodied sense of normality. It makes you very conscious about the brittle grounds on which our society and economy are built. Frankly, it should not come as a surprise. It's been on the horizon for years. Yet it still comes as a felt shock. Suddenly, our generational tensions, our economic inequalities, our moral comfort zone... we will need uncomfortably honest Philosophy more than ever now. To use the rather apt title of an Austrian movie: "Die fetten Jahre sind vorbei."

Last meal? What are you drinking?

Wine - a Sforzato, from North Italy, made from dried grapes. Divine. And with it, all the stinky cheeses, soft cheeses, all kinds of them! Maybe, as the main dish, Thüringer Klösse with red cabbage and deer goulash. And dessert: Crème brûlée. Great, I am hungry now.

If you could as an omniscient being one question, and be sure you were going to get an honest, comprehensible, answer, what would it be?

What’s it like to think like Tesla?

[interviewer: Cliff Sosis]