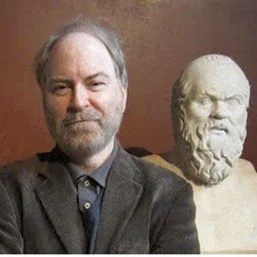

In this interview, Shaun Gallagher, Lillian and Morrie Moss Professor of Philosophy at the University of Memphis, talks about growing up in Philly, Catholic school, summer on the Jersey shore, considering becoming a cowboy (or philosopher), JFK, Janis Joplin, studying theology as an undergrad at St. Columban’s, Vietnam and institutional religion, bad faith and existentialism, a stint as a private detective, pursuing his PhD at Bryn Mawr, summers in Ireland (where his parents were from), working with José Ferrater-Mora, Merleau-Ponty, becoming more aware of the relevance of science, his first publication, getting 8 interviews at the APA smoker and 1 job offer, phenomenology, cognitive science, and the value of interdisciplinary approaches, embodied, embedded, extended, and enactive cognition, what drives him, Parmenides, and the meaning of life…

[10/27/2025]

What was your earliest memory?

The ticking of an alarm clock next to my bed – or so I think. Memory is tricky. I think it may be odd that it’s an auditory memory. But I sometimes think this could be a reason for my philosophical interest in time.

Where did you grow up? What did your parents do, and what was your family like?

I was born and grew up in Philadelphia – West Philly and the western suburbs. I lived there until I went off to college in Wisconsin.

My parents were immigrants from Ireland. They had very little formal education. My father was a farmer, fisherman, and construction worker before he came to the US. After working as a grave digger for a couple of years in Philadelphia he got a job on the night shift in a factory where they printed the Saturday Evening Post. He also worked as a landscaper. He worked two jobs for most of his life, leaving for the factory around 3pm, getting home after midnight, getting up in the morning around 6:30 to go out landscaping. My mother worked part-time doing domestic work for rich families on the Philadelphia Main Line. This, it seems, was better than being poor in rural Ireland, or getting temporary jobs in the UK. When I was 13 they took me “home” to Ireland for a month, to the place where they came from, and I was shocked at how beautiful it was. It must have been a real culture shock for them moving to a big city like Philadelphia.

They came to Philadelphia because they had brothers and sisters already living there. The whole family were hard-working, blue-collar and very Catholic. My sister and I, and our cousins all went to Catholic schools, went to Mass every Sunday. We would spend part of the summer holidays at the Jersey shore (South Jersey) – aunts, uncles, cousins all getting sunburned on the beach. That was before there was sunscreen.

As a little kid, what do you think, or what did others think, made you unique?

I don’t think I thought of myself as unique, and no one told me I was unique. In school I excelled in geometry, but not so much in algebra. In grade school I always did well in religion class.

What did you want to be when you grew up?

A cowboy, a fireman, a private detective, an engineer, a priest, a philosopher – in that order.

Nice. Favorite classes or teachers in high school?

Geometry yes; algebra no. Calculus was strangely okay. My English teacher got me interested in civil rights. One of his assignments was to go to a CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) meeting in Philadelphia to interview activists and report back. And my Latin teacher declared one “philosopher’s holiday” every semester where he would teach us about philosophy – mainly St. Augustine and Aquinas.

Extracurriculars?

Football and softball in grade school, to the extent I knew I would not make the high school teams; but I did play soccer for one semester.

What was on your mind outside of school?

Girls.

Word. As a teen, what else were you passionate about, if anything?

I really liked to read. Novels especially. And secretly I wrote novels, but I could never finish them.

Favorite author or authors from back then?

Hemingway, Faulkner, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and then later Sartre, Camus, Stendhal. These are all the serious authors, but I also read a huge amount of Ian Fleming.

What else were you into?

Politics. I was a teenager when JFK was assassinated and that shook me. I had gone to a meeting to see him when he was running for president.

Were you affected by other world events, or technological, or cultural developments, growing up?

The other political assassinations – RFK, MLK. Civil Rights. Television.

What did you do for fun? Get in trouble?

I’m sorry to say I didn’t get in trouble. Music for fun. Beatles first. Janis Joplin and Grateful Dead later. Maybe I did get into trouble later on, but nothing unusual.

What did you worry about?

I worried about being on time.

Where did you apply to college and why?

Trinity College, Dublin, because I was Irish (I’m an Irish citizen and have an Irish passport) and thought it would be cool to live in Dublin. Villanova University because I had a passing fantasy that I would like to be a chemical engineer. St. Columban’s College, a Catholic seminary, because I had a passing fantasy that I would like to be a priest.

For your undergrad education, you went to St. Columban's. Why did you end up not becoming a priest?

It was the 60s and everything was up for grabs. I did some social work. I attended some protests. I converted to a different form of idealism. I broke a lot of rules in order to protest them. I listened to Bob Dylan. And I was forced to study philosophy, because that was preparation for studying theology. That was the most significant thing. They forced me to study philosophy and I loved it. It was like they opened a door and I was able to walk out.

Elaborate, please.

Well philosophy, from the church’s perspective, was meant to support theological studies; but for me it led me away from theology. I was reading Aristotle and the existentialists and that was more interesting than the scholastic philosophy covered in most of my courses. But even more so, given the times – the Vietnam war, political turmoil – I didn’t think institutional religion offered very much. The hierarchical superstructure didn’t support the kinds of bottom-up religious-based movements that were trying to address poverty and injustice, so one could easily get involved in small internal squabbles that distracted and derailed attempts to do anything meaningful.

Pleasant surprises? What did you do for fun?

I have to take the 5th on that. It was the 60s.

Inspirational classes or teachers?

Cyril Svoboda, who later taught at the University of Maryland. He was a double PhD in psychology and philosophy. His Existentialism course. I had been giving most of my attention to reading Aristotle and suddenly I had to add Sartre and Camus.

So, Camus, Sartre, was it the atheism thing that got you into philosophy? What's your favorite bit of existential writing?

It wasn’t atheism. It was the ontology, and Sartre’s analysis of bad faith that seemed so different from the other philosophers I was reading — I mean Aquinas, Descartes, Kant.

Personal or academic challenges?

Languages. I’ve studied Latin, Spanish, French and German, but I’ve never done well or become fluent in any of them.

Earlier, you said as a kid you were interested in becoming a philosopher. As an undergrad, when did you decide to commit to philosophy exactly?

It’s difficult to say. I know I read much beyond my course work for the philosophy major. I was motivated enough to do a Master’s degree, and once I started that I was hooked. Good teachers again. Thomas Busch (for Sartre and Merleau-Ponty), Jack Caputo (for Husserl and Heidegger), and John Tich, whose course on Nietzsche was mainly about the Greeks (whom he could recite from memory in the original Greek) and Heidegger.

What did your parents make of this decision?

They were cool with it since they didn’t know what philosophy was.

Ha! Did you ever consider doing anything else?

Yes, I was a private detective for about three years. I worked for an agency investigating bank fraud among other things and I thought about getting my own license. Although I didn’t solve many cases the agency thought I was quite good because I knew how to write and they required written reports to keep their clients happy. There was a moment I considered going to law school, but my experience testifying in court on these bank cases quickly changed my mind.

What was the experience testifying like?

Testifying in court as an expert witness — or at least as someone who was familiar with the complexities of the various bank-related crimes — was always interesting, but it was strictly reporting the facts of the case and explaining to the court precisely what was done. So not extremely exciting.

If you could go back in time, and give yourself advice back then, what would it be?

I often think about this but I conclude that I don’t want to offer advice to my past self because I would likely want to do things differently. But if I did things differently my life (with which I am quite happy today) would likely be quite different. So why mess with a good thing?

Sure. When did you decide to go for the PhD? Where did you want to go and why? Receive any guidance on that front?

After college I worked for a year in Wisconsin as a land surveyor. With friends I went to Europe for a summer. Then I went back home to Philadelphia and worked for another year before deciding to do the Masters, which I did at Villanova. I continued to work as I studied for the MA – I don’t think there was any funding available, although Villanova gave me a tuition waiver.

What did you focus on at Villanova?

Phenomenology. I wrote my first published article there on Husserl’s phenomenology of time-consciousness.

Surprises?

The community of students and professors were super friendly and helpful. It was a great place to do the MA. More recently I was surprised to learn that the current Pope was a student at Villanova at the same time. He did some philosophy courses as an undergraduate there – I think Caputo was one of his teachers. But I never met him, as far as I know.

Philosophically, what was trending at Villanova?

Phenomenology. Husserl, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty and Sartre. It wasn’t yet post-phenomenological continental philosophy. There was history of philosophy and some analytic and social-political philosophy, but my focus was on phenomenology.

And when’d you start contemplating a PhD?

I did well enough in my studies that my professors encouraged me to go on for a PhD. Jack Caputo did his PhD at Bryn Mawr and suggested I go there. It was down the road and since I was working in Philadelphia I thought I would give it a try. In my second year at Bryn Mawr they gave me full funding and I was able to quit my detective job and spend full time with philosophy, which was heaven. I had been able to save enough money from working to buy an old house in Ireland, and so, starting when I started at Bryn Mawr, I would spend my summers in Ireland reading, writing, and fixing up the house. From there I sometimes went to Europe to study German or philosophy.

Why did Jack Caputo think Bryn Mawr would be a good fit?

Well, that’s where he did his PhD and he suggested that my interests fit well with José Ferrater-Mora, a Spanish philosopher who taught there. And he was right. José knew everything about everything — he wrote a famous dictionary of philosophy.

You make buying a house in Ireland sound like buying a used car. Please, explain!

As I mentioned my parents came from Ireland, and I visited when I was younger and really fell in love with the place. I heard that an old house was for sale. It was located on the Northwestern coast in Donegal, in a small village on a peninsula, with the sea on one side and hills on the other. This was very close to my parents’ original homes, and I had many cousins living nearby, so people considered me almost like a local. The house required a lot of maintenance because of its proximity to the sea. So I spend most of my time there fixing it up.

What was up at Bryn Mawr?

The nice thing about Bryn Mawr was that you could study what you wanted. My primary interests continued to be phenomenology, embodied cognition and temporality. This led me to read a lot of Merleau-Ponty, and that motivated me to take seminars in neuroscience and psychology in addition to my philosophy seminars. But there was also the opportunity to study pragmatism. I studied Peirce, James, Dewey, Royce, and Mead with Isabel Stearns. George Kline helped me work through Hegel and Whitehead. I studied Kant with Ferrater-Mora.

What was the dissertation on?

The phenomenology of temporality and embodiment. I engaged with the classic phenomenologists — Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty — and with the most recent science, with the idea of updating Merleau-Ponty who incorporated a lot of neurology and psychology in his phenomenological studies.

Enjoy the process?

Yes. Some of my fellow grad students seemed to spend a lot of time complaining — I don’t even remember what they were complaining about. But I loved it. Reading and writing philosophy — what could be better?

Advice for graduate students?

If you love it, go for it. Otherwise forget it.

Were you encouraged to publish?

Not really.

What were your fellow grad students like?

Very cool, and weird — in a good way.

Who did you hang out with and what did you do to unwind?

It really changed from one year to the next. I had a girlfriend — also a philosopher. I stayed with her some of the time. I lived with a group of Irish guys for some of the time. I spent time in Ireland and in Europe. I studied German in Germany and twice attended the Collegium Phaenomenologicum, a month-long meeting in Perugia, Italy. I spent a semester in Louvain when I was writing my dissertation.

How did you change, philosophically? Personally? Struggles? Victories?

I learned a lot and practiced my writing. I grew to appreciate the history of philosophy and at the same time I found I liked to focus on specific issues. I definitely started to see the relevance of the empirical sciences through my study of Merleau-Ponty, but I wasn’t yet attuned to the cognitive sciences — that came later.

What was the market like when you finished?

The job market was very tight when I was finished, but not as tight as it is today. My professors would tell me stories of how they would be contacted before they graduated an offered a job over the telephone. So compared to that, the market was tight. But after finishing I had 8 interviews at the APA, and one job offer out of that.

Job market horror stories?

Only the APA smokers which were filled with anxiety and lots of smoke.

Anybody help you out?

Not really.

Where did you land your first gig?

I got a one-year position at Gwynedd Mercy College, which is now Gwynedd Mercy University. Then I got a three-year position at Canisius College, a Jesuit institution, now Canisius University in Buffalo. That turned into a tenure-track position.

What was your first time teaching like?

Lots of fun. I used lecture notes and was quite surprised when students asked me questions.

I am unfamiliar with the work of Merleau-Ponty. I have no doubt there is good stuff there, but I think many philosophers are simply unaware of it. What should we read by Merleau-Ponty and why? What does he contribute to philosophy?

Merleau-Ponty is difficult to read because of his flowery French prose and his detailed consideration of the positions that he disagrees with. But then you find brilliant insights that make the struggle worthwhile. I like his earlier work – The Structure of Behavior and Phenomenology of Perception. But also his Nature Lectures which were part of his later work but covered so many interesting topics. He is most well-known for his emphasis on the body and is really a forerunner of embodied cognition. He also approaches the topic using not only phenomenology, but empirical studies in psychology, developmental psychology, neurology and psychiatry. My sense is that he was doing cognitive science, at least an embodied type of cognitive science, before there was cognitive science.

Explain what phenomenology is, for those who may be unfamiliar with the idea.

Phenomenology, as a historic school of thought started with Husserl. He was trained as a mathematician, and he studied psychology with Brentano and Carl Stumpf, and was influenced by William James. He attempted to work out a transcendental approach to consciousness. He focused on the intrinsic temporal structure and the intentionality of consciousness, the idea that consciousness is always about something or directed towards an object. He developed a phenomenological method and then analyzed a broad range of experiences, including intersubjective empathy. He had a great influence on Heidegger, who was his academic assistant for a time. Heidegger thought of phenomenology somewhat differently and applied it in his fundamental ontology – that is, the ontology of human existence – which was an existential-hermeneutical analysis. He influenced the French existentialists, especially Sartre, who was also influenced by Husserl. Sartre produced a phenomenological existential analysis of many of the same themes that Husserl dealt with – temporality, intentionality, intersubjectivity, embodiment. Merleau-Ponty, under the same influences, used the notion of embodiment, to deal with these same topics. Also influenced by Heidegger, Gadamer developed the hermeneutical side of this thinking. I mention all of these thinkers to suggest that phenomenology isn’t any one thing – it’s a broad philosophical concept that has motivated developments in existentialism, hermeneutics, and then embodied cognition. Accordingly, it’s difficult to define. I would add that various forms of post-structuralism developed in response to, and sometimes in opposition to phenomenology.

Do you think analytic philosophers are less afraid of phenomenology nowadays? Hermeneutics?

There still is something of an analytic-continental divide – a kind of mutual indifference (when it’s not antagonism) between analytic philosophers and those on the continental side. I think, however, that in some limited areas, such as philosophy of mind, there has been more conversation between phenomenology and analytic philosophy. I attribute this to the fact that both sides are reading the same empirical literature and trying to make sense of it. Plus I think that analytic philosophers of mind and phenomenologists have, over the years, met at interdisciplinary conferences and have had personal conversations – so there may be more openness even if not necessarily agreement on everything. These kinds of personal meetings have a history to them. Husserl and Frege corresponded with each other; Heidegger met with Carnap; Merleau-Ponty organized a meeting at Royaumont, just outside of Paris -- a colloquium on analytic philosophy in 1958 that included not only phenomenologists but also a group from Oxford – Ryle, Ayer, Quine, Austin, and others. My own contribution to this kind of dialogue was a symposium that I organized with Francisco Varela in Paris in 2000. We invited phenomenologists, like Dan Zahavi, Eduard Marbach, Natalie Depraz and Jean Petitot and analytic philosophers like José Bermúdez, Naomi Eilan, Tamar Gendler, John Campbell and others to a discussion of perception and embodied cognition. I think it was helpful that we were discussing some of the same empirical studies.

Limitations of these approaches?

Every approach and every methodology has limits. They sometimes bump up against such limits when they encounter a different approach or method. Then they have to cope. Without trying to sound too Hegelian, I would want to say that bumping into limitations in this way is a good thing, and it helps to transform philosophy. It’s analogous to how language functions. It’s limited because, on its own, it can’t do any non-linguistic things – it can’t transport you from one city to another, and it can’t manufacture goods, etc. Yet you also have to say that language is unlimited in the way it works – we never run out of things to say, and we always find new language to say such things. Moreover, language clearly helps us to do those other non-linguistic things. Likewise, neither phenomenology nor philosophy of mind can be neuroscience or psychology, or literature or art. Such limitations are what motivates the attempt to take an interdisciplinary approach, which, in turn, can be where philosophy contributes to the work of the other disciplines.

In retrospect, what three or four things were you most proud of during the time you spent at Canisius College? You spent a decade at Buffalo before you moved to University of Central Florida. Why the change?

In terms of my academic work I wrote and published Hermeneutics and Education (1992) and The Inordinance of Time (1989) when I was at Canisius. I also published several papers that have had a significant impact (if citations are any evidence for this) in the areas of cognitive science and social cognition (for example, “Philosophical Conceptions of the Self” in Trends in Cognitive Science; and “The practice of mind” in Journal of Consciousness Studies). Much of the research for those papers resulted from a visiting research stay at Cambridge and an NEH Summer Seminar at Cornell. I also started a family and with my wife Elaine raised two daughters. Because Elaine and I both had faculty positions at Canisius (she was Associate Professor of Art History) we stayed there for a good while. At the end, Elaine wanted to move on from academics; Canisius was not really able to support my research and the teaching schedule was very heavy, so when the opportunity presented itself to move to Florida we went for it. I was hired as department chair at UCF, and the dean recognized that I was doing a lot of research and publishing, so she gave me a very reduced teaching load.

And what work were you most proud of during your time at UCF? How were these departments different? Similar? How have the students changed during the course of your career?

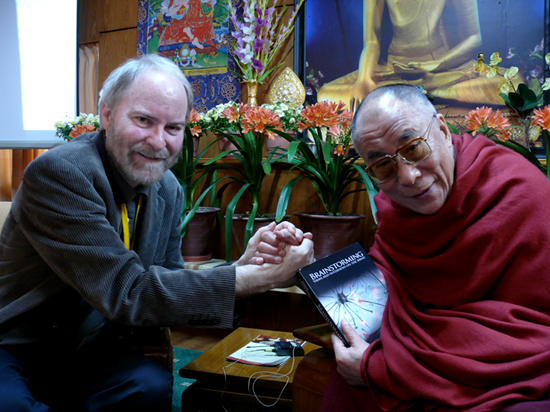

UCF emphasized funded research a lot more than Canisius. While I was at UCF I made a successful grant application to the Templeton Foundation to fund a neurophenomenological study of awe and wonder during space travel (UCF is the closest university to the Kennedy Space Center, so there was a significant interest in the space program reflected in UCF research). Because I was also appointed a Research Professor at the University of Hertfordshire in the UK I was able to apply for a large Marie Curie grant as part of an Actions Network, and this led to other grants from the European Research foundation and NSF in the States. UCF allowed me the freedom to pursue these projects, and to accept visiting positions in Copenhagen, Paris, Lyon, Aarhus, Prague and Berlin.

Why the move to Tennessee?

Memphis made me an offer I couldn’t refuse – especially in terms of research funding and teaching load, but also the chance to teach in a PhD philosophy program, which wasn’t available at UCF.

How have students changed over the years?

I did a lot of teaching at Canisius and not so much at UCF. I’m teaching almost exclusively PhD students at University of Memphis. As a result, I have a hard time saying how students have changed over the years although I’ve always enjoyed teaching and engaging with students. One thing that stays the same is simply that some students engage more than others.

You meditate, right? Benefits? Therapy? Should everybody go to therapy?

I don’t meditate consistently. It’s an occasional practice. It helps with stress. I’m not in therapy (although I think my writing is a sort of therapy – at least it’s one among other things that keep me happy). I have to confess I’ve been very lucky in life and privileged in my career. My parents definitely had a harder time of it. And yes, everyone should go to therapy, except me.

What is the relationship between neuroscience and philosophy, specifically, phenomenology?

Phenomenology and philosophy of mind can certainly learn from the empirical sciences, and I think vice versa. I have referred to this as a kind of “mutual enlightenment.” To the extent that neuroscientists are interested in explaining emotion, or perception, or memory, or action, phenomenology provides some clarification about what they are trying to study. It’s not enough to say that some set of neurons are activated; and if psychology can say what sort of behavior correlates with such activations, phenomenology offers a systematic way to characterize the experiential aspects of those processes.

Husserl himself suggested that whatever work he was doing in transcendental phenomenology could be explored in the natural sciences by effecting a change of attitude, i.e., from a transcendental to a naturalistic attitude. Likewise, Sartre combined phenomenology with empirical studies of imagination; and Gurwitsch and Merleau-Ponty did the same. I know there is a debate about naturalizing phenomenology, but in response to skeptics about that I always point to these phenomenologists who were already engaging with the science.

Can phenomenologists learn anything from science?

I think the answer is clearly yes. One can consider specific discoveries in the sciences that motivate further phenomenological reflection on conditions such as unilateral neglect, deafferentation, depression, schizophrenia, somatoparaphrenia, etc. as well as experiments on change blindness, the Rubber Hand Illusion, out of body experiences, etc. I’m mentioning topics that I’ve written about or have taught.

Can science learn anything from phenomenology?

Besides the mutual enlightenment idea, I think that phenomenology pushes us to reconsider how we conceive of nature. Rather than something “out there,” and objectively existing, nature is something that is always mediated by subjective experience because we are part of the nature that we are trying to understand. Merleau-Ponty raises this issue in his very first book, The Structure of Behavior, where he thinks that we need to rethink the very concept of nature in a way that is not reducible to the standard scientific conception of it.

You seemed to be more and more interested in extended or distributed cognition. Do you think cognition, or thinking, includes activity outside of the brain, including not just the body, but institutions?

I am more and more interested in 4E (embodied, embedded, extended, enactive) cognition. For cognition, the unit of explanation needs to be brain-body-environment (where environment includes social, cultural and normative factors) – admittedly a hugely complex system. The brain hasn’t evolved on its own – it’s always been part of a body which is always part of an environment. 4E cognition gives us several ways to think about all of this. Clark and Chalmers’ extended mind hypothesis is part of this – and of course is subject to many interesting debates. I’ve proposed to integrate social factors in the form of the socially extended mind (SEM), which extends cognition to include not just tools and technologies, but social and cultural institutions that have epistemic functions and help us solve problems. This could include something like the legal system. And more recently I’ve been working with co-authors Enrico Petracca and Antonio Mastrogiorgio in the area of institutional economics where the market can be thought of as a cognitive institution.

Is it possible to define cognition too widely?

Yes.

Is the ecosystem thinking?

No.

Why not?

So on the one hand it depends on how inclusive you want to be. Some enactivists will say that even bacteria are in some way cognitive insofar as they respond to environmental factors. So that’s a very basic conception of cognition, but it doesn’t mean that a bacterium or the ecosystem is engaged in thinking, which seems to me to be a more sophisticated process than basic cognition. On the other hand, some critics of extended mind will say that on the extended mind hypothesis even the internet seems to be engaged in cognitive processes – this is known as the “cognitive bloat” objection. In this respect, if one focuses on human cognition, as I tend to do, then one answer is that tools and technologies play a role in cognition only when we engage with them. So I think there are overly narrow ways to define human cognition, and overly wide ways to define it, but answering these questions really get complicated when we start to think about animal cognition and artificial intelligence.

You are very productive. It's bananas, man! What drives you? What's your routine?

I really enjoy writing philosophy. It’s as simple as that. It makes me happy. My routine is to start in the morning, usually checking my email and responding to any legitimate requests. If I have to take care of academic business, I push that off until late afternoon if I can. I work best in the morning. I eat breakfast (sometimes bananas) but I don’t usually eat lunch. When my wife and I are in the same city, I have dinner with her most evenings – sometimes we go out. In Memphis I usually cook dinner unless I have to go out with colleagues. I rarely work after dinner. I either read or go to the screen (television or films). I like the dark Scandinavian shows like The Killing. When I have visitors in town I like to go to nice restaurants and then to the blues clubs.

What projects are on the horizon?

I just finished a book (now under review) with Enrico and Antonio, on SEM and institutional economics. I’m also working with Albert Newen at Ruhr University-Bochum on a book in philosophy of mind with some funding from the Humboldt Foundation. For the past few years I’ve been a visiting professor at the University of Rome – sometimes in the Psychology Department at Sapienza, and sometimes at the Philosophy Department at Roma-Tre. This has been extremely productive. With Guido Baggio at Roma-Tre, for example, I’ve organized a series of workshops on 4E cognition and economics and I’ve been working with Riccardo Viale on an enactive approach to problem solving in economics. And at Sapienza I’ve been working closely with the psychologist Antonino Raffone and the neuroscientist Salvatore Aglioti. We’ve recently published a paper on compassion in Trends in Cognitive Science, and we are currently working on several other projects together, including a paper on bodily self-awareness. Most of my collaborations are in Europe, so I’ve been spending a lot of time there. Also, over the past ten years I’ve been a Professorial Fellow at the University of Wollongong in Australia and I’ve been spending a month every year there (except for the pandemic years). I hope to be able to continue doing that, because working with Dan Hutto there has been very productive for our work on enactive philosophy.

You can only save two books or articles you've written from being erased from human memory, what are they, and why?

Well that’s sad news. I suppose I would be tempted to say How the Body Shapes the Mind and the TICS article “Philosophical conceptions of the self” because these are my most cited book and article. Together they’ve been cited close to 11,000 times. That means that if they were erased a lot of other people’s work might be affected. So that’s a kind of utilitarian argument. But also my work with Dan Zahavi, The Phenomenological Mind, has been cited more than the TICS article, and that would have a large impact on my friend Dan. But he’s written so many other books, perhaps it doesn’t matter – assuming you are not going to erase them too.

Between the time you left grad school, and now, how has the philosophical landscape changed? Like, how have things gotten better? Worse? For grad students and faculty, and philosophy as a whole?

For grad students there are fewer jobs. For faculty, a lot more pressure to publish and to apply for grants. Philosophy as a whole is always threatened – programs disappearing in budget cuts or reorganizations of faculty. Medieval times were much better for philosophy – and of course much worse as well. Let me say that one thing that has improved is the number of underrepresented groups in the profession (with two provisos: first, there is still some distance to go; and second, the last 8 months in the US has involved a giant step backwards) I want to note that the University of Memphis has been doing its part in this. There was a study in 2014 (now somewhat out of date) indicating that Memphis produced more African-American PhDs in philosophy, and more women PhD’s in philosophy than any other American university. I’m not sure what the numbers are now, but I know that we’ve awarded over 20 PhD degrees to African-Americans, and we are trying to continue our work in that area.

Best philosopher you vehemently disagree with?

Don’t all philosophers disagree with other philosophers all the time? Maybe ‘vehemently’ is the key word here. I highly respected but also vehemently disagree with Alvin Goldman. I still respect his work, but don’t disagree with him anymore since he recently died, and I’m sure saw the light.

Most overrated philosopher, historically?

Parmenides. He had one interesting idea but was unable to change with the times.

Ha! Favorite living philosopher?

It’s hard to keep up because philosophers keep dying. It’s also hard to say because philosophers do different things and my favorite in one area may not be my favorite in another. My daughters used to ask me what my favorite color was. I told them green for grass, blue for sky, bluish-green for the sea, etc. etc. The other problem is that I know a good number of philosophers personally, and I don’t think I can name one as my favorite without upsetting others (maybe, if they care what I think). Finally, I have to say I don’t really have a favorite. I seem not to think in those terms.

How do you see the future of philosophy, in general?

It’s really difficult to come up with a new idea. It may be that new technologies will continue to force philosophers to think or rethink certain issues. I suppose the new AI will do something like that. So maybe we should ask ChatGPT about the future.

Meaning of life, in your estimation? Afraid of death?

I’m not sure what the meaning of life is, but I am sure it has something to do with how we relate to others. Not afraid of death, but deathly afraid of dying.

Last meal?

Pizza from a place in Trastevere called Cave Canem.

You have the opportunity to ask an omniscient being one question and get an honest answer, what's the question?

I would resist the temptation to ask a philosophical question and instead ask a practical one, such as, what is the cure for pancreatic cancer. I know too many people who have died of that cancer.

Thanks for your time, Shaun.

[interviewer: Cliff Sosis]